Your Upbringing May Impact Your Love Life

Are you trying to navigate life as a Multi-Cultural Couple: Hint* – If yes, you should know that there are hidden influences!

Culture has traditionally been defined as the shared beliefs, practices, and social conventions of a particular group of individuals. In recent years, however, the term cultural identity has increasingly been used interchangeably with socioeconomic status, health and physical differences, neurodiversity, politics, gender, sexual identity, and more.

Baskerville (2022) argues that some cultural identities may be consciously or unconsciously kept outside of our self-representations due to systemic oppression. As Dhananjaya (2022) insightfully noted, "We carry multiple identities that are internally constructed and interact within us at intrapsychic, interpersonal, and intersectional levels. The power dynamics among these internal identities are active and significantly impact how we engage with the world" (p. 247). Thus, how our multiple internal identities, which I refer to as multicultural identities for the purposes of this article, result in unique combinations of discrimination and privilege has been sociologically termed as intersectionality (Crenshaw,1989).

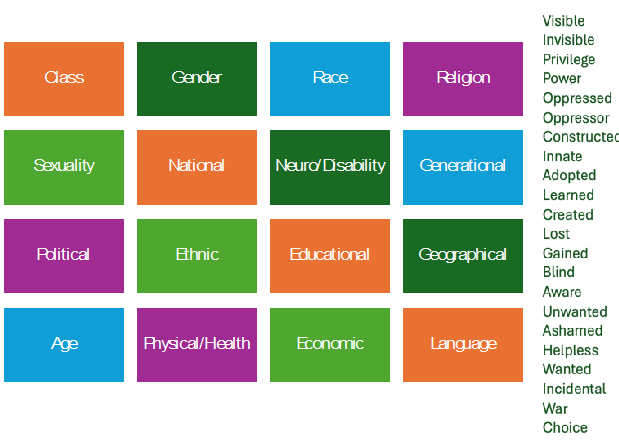

I encourage the reader to consider the ways in which they relate to their various cultural selves by utilizing the list of words that are appended to the grid below:

Continuing this conversation, I would like to introduce an additional aspect that frequently manifests as a ‘hidden’ cultural identity, commonly referred to as the Third Culture.

The term "Third Culture Kids" was originally introduced by Van Reken & Pollock (2017) to describe children who were raised in a culture different from their own and different from that of their parents.

In this context, it refers to a state of existence that can be best defined as a liminal state, where individuals feel a sense of not belonging to neither their original culture nor to the one they were raised in. Van Reken & Pollock (2017) recently introduced the term "Cross Cultural Kids" to encompass a broader understanding of culture and intersectionality. They defined it as an individual who has resided in, or had significant interactions with, two or more cultural settings for a substantial duration during their formative years.

The premise of my argument is that this idea is applicable to individuals who have extensively engaged with a culture, in its broadest sense as mentioned above, and consequently formed shared similarities with others who have had similar experiences. However, within the Third Culture context, these shared commonalities often remain as hidden aspects of their identity as the notion Third Culture simply refers to a neither/nor world.

Another form of complexity arises from the implicitly acquired and culturally reinforced variations in how we navigate the interaction between ourselves and others.

The two common personality aspects, self and relatedness (I-Other), have been at the center of personality theories in many areas of psychology, ranging from cross-cultural to social psychology and psychoanalysis.

Blatt & Schichman (1983) suggest that personality develops through a complicated dialogue between two dimensions:

- Self-definition (I)

- Interpersonal relatedness (Other).

This implies that Interpersonal relatedness leads to the growth of more mature, close, mutually satisfying, and reciprocal relationships with other people, whereas self-definition is the basis for growth of a more distinct, integrated, realistic, and essential self. My contention is that our position on this duality is often influenced by the intersection of cultural identities that we are not consciously cognizant of.

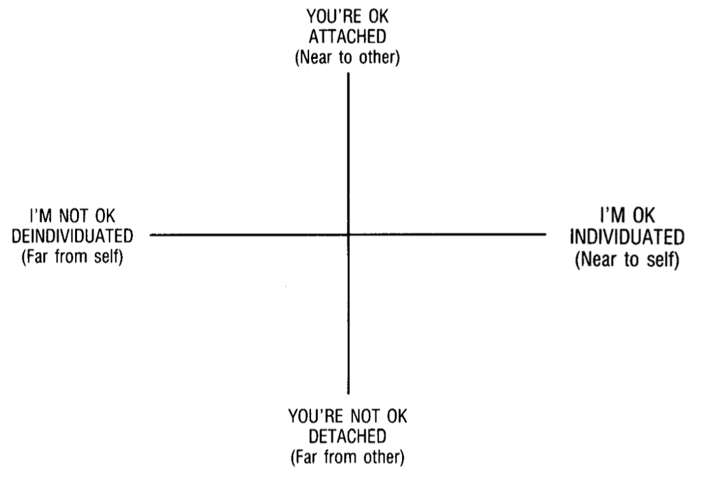

Joines' (1988) model of the OK Corral is the most appropriate method to understand this division within a theoretical framework of Transactional Analysis.

Figure 2

A bidimensional view of interpersonal distance superimposed upon a unidimensional one (Joines, 1988, adapted from Kaplan, Capace, & Clyde, 1984, p. 115)

In Joines' (1988) interpretation of Ernst's (1971) OK Corral, individuals position themselves along a relational continuum, and their level of well-being is determined by their self-definition. The horizontal axis represents the continuum of individuation, with the "I'm OK" end indicating a state of being close to oneself, and the "I'm Not OK" end indicating a state of being distant from oneself, known as deindividuation. The concept of attachment was incorporated into the vertical axis, where the end labeled "You're OK with me" represents relatedness (proximity to others) and the end labeled "You're Not OK" represents detachment (distance from others).

I've called this model the "intersectional life position" because it effectively illustrates the "I-Other" dichotomy which, I argue, can also be intersectionally determined. For instance, in my culture of origin (Turkish), the Cultural Parent (Drego, 1983) dictates that we need to put the other first in this equation. This translates into I am OK with You – I am Not OK with Me position, with the hope that this will be reciprocated by the other to maintain a mutually created form of OKness.

When I am in Turkey, I tend to automatically code switch (Baskerville, 2022) to this position, whereas in Boston, where I am currently local, I can comfortably operate from an I am OK with Me - You are OK with Me position.

So, what's really shaping the dynamics in multicultural couples?It goes way beyond just individual personalities.

Research dives into the powerful impact of the "Cultural Parent" (Drego, 1983) – the ingrained beliefs, values, and behaviors we absorb from our cultural backgrounds.

Our parental messages influence us, along with other voices from our past. These may be ‘various voices’ from our childhood hometown, our wider family, sports coaches, governmental messages, teachers and so on.

In Transactional Analysis, we call these influences the Cultural Parent. Cultural Parent shapes our expectations in relationships, communication styles, and even how we express love. These influences are often invisible, leading to misunderstandings and conflict if not addressed.

In my view, when working with multicultural couples in therapy, recognizing the Cultural Parent is key. We do so by paying attention to the following factors:

- Cultural Identity is Complex:Acknowledge the multifaceted nature of cultural identity (race, ethnicity, gender, class, religion, etc.) in each partner.

- Implicit vs. Explicit Communication:Pay attention to how cultural backgrounds influence communication styles (direct vs. indirect, expressive vs. reserved).

- Power Dynamics:Explore how cultural norms around power, privilege, and oppression might be playing out in the relationship.

- Generational Influences:Recognize that cultural values and beliefs are often passed down through generations, shaping each partner's "Cultural Parent."

This allows partners to:

- Unpack Assumptions:Identify where their expectations come from and how they differ.

- Improve Communication:Bridge the gap between implicit and explicit communication styles shaped by culture.

- Build Empathy:Develop deeper understanding and respect for each other's backgrounds.

- Create a Shared Culture:Consciously build a relationship culture that honors both individual and collective values.

- Education as a Metaphor:Consider how each partner's "educational script" (their past learning experiences) influences how they approach growth and change within the relationship

Understanding these dynamics can transform conflict into connection, fostering stronger and more resilient partnerships.

You can find more good stuff on my blog: https://drkelestherapy.com/blog

#multiculturalcouples #couplestherapy #culturaldiversity #relationships #communication #intimacy #crossculturalrelationships #culturaldifferencesinmarriage #mentalhealth #diversityandinclusion #crosscultural #therapy #transactionalanalysis #couplestherapy #taisevidencebased

References

- Baskerville, V. (2022). A Transcultural and Intersectional Ego State Model of the Self: The Influence of Transcultural and Intersectional Identity on Self and Other, Transactional Analysis Journal, 52:3, 228-243.

- Blatt, S. & Shichman, S. (1983), Two primary configurations of psychopathology. Psychoanal. Contemp. Thought, 6:187–254.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics.1 University of Chicago Legal Forum, Issue 1, Article 8.2

- Dhananjaya, D. (2022). We Are the Oppressor and the Oppressed: The Interplay Between Intrapsychic, Interpersonal, and Societal Intersectionality, Transactional Analysis Journal, 52(3), 244-258.

- Drego, P. (1983). The cultural parent. Transactional Analysis Journal, 13(4), 224–227.

- Joines, V. (1988). Diagnosis and Treatment Planning Using a Transactional Analysis Framework, Transactional Analysis Journal, 18(3),3 185-190.

- Van Reken, R. E.; Pollock, D. C.; Pollock, M. V. (2017). Third Culture Kids 3rd Edition. Quercus.